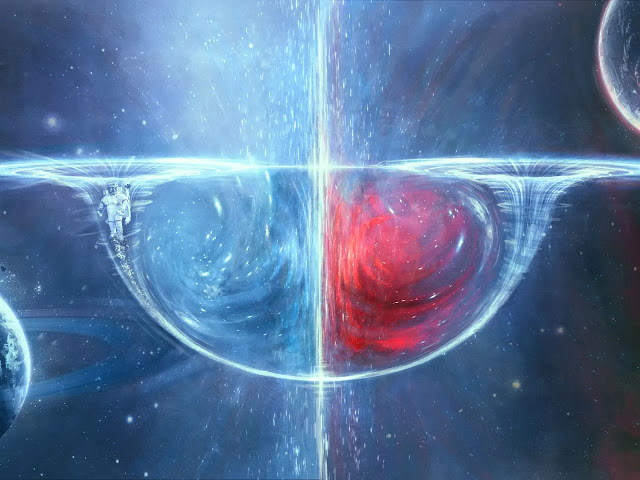

Black holes, which are wormholes that hypothetically connect one region of the universe to another, may be hidden in plain sight, according to a group of physicists from Sofia University in Bulgaria, according to New Scientist.

crossorigin="anonymous">

style="display:block"

data-ad-client="ca-pub-2375157903127664"

data-ad-slot="7629783868"

data-ad-format="auto"

data-full-width-responsive="true">

Scientists have long been perplexed by black holes since they consume stuff and prevent it from leaving.

But where does this whole thing go? The possibility that these black holes are leading to "white holes," or wells that emit streams of particles and radiation, has long been considered by physicists.

These two ends may come together to create a wormhole, or an Einstein-Rosen bridge, which some physicists think might extend any length of time and space. This intriguing hypothesis has the potential to change the way that spacetime works as we now understand it.

Now, the scientists propose that a wormhole's "throat" may resemble previously identified black holes, such as the monstrous Sagittarius A* that is thought to be lurking in the heart of our galaxy.

Petya Nedkova, team leader at Sofia University, told New Scientist that wormholes were just the stuff of science fiction ten years ago. "People are eagerly looking for new scientific horizons as they come forth now."

crossorigin="anonymous">style="display:block"

data-ad-client="ca-pub-2375157903127664"

data-ad-slot="7629783868"

data-ad-format="auto"

data-full-width-responsive="true">

The team's newly created computer model predicts that the radiation coming from the matter discs spinning around the edges of wormholes may be almost hard to differentiate from that surrounding a black hole, as described in a recent research published in the journal Physical Review D.

According to their calculations, the difference between the amount of light polarization released by a black hole and a wormhole would really be less than 4%.

According to Nedkova, "With the existing observations, you cannot identify whether a black hole or a wormhole is there; there may be a wormhole there, but we cannot tell the difference." Therefore, we were hunting for anything else in the sky that would help us tell black holes apart from wormholes.

While Nedkova and her colleagues hypothesize that future observations could help to discriminate between them. We might, for instance, search for any light that could be leaking in from the other end of the wormhole or coming out of the black hole as little rings of light.

But as of this present, we just lack the equipment necessary to conduct those types of close-range studies of black holes.

The only way to know for sure would be to use an even more precise telescope to detect these cosmic anomalies.

Of course, the alternative is to risk it all by falling into a black hole.

Nedkova reportedly said to the magazine, "If you were around, you would find out too late." "You'll learn the difference when you either pass through or perish."

Comments

Post a Comment